There's a certain delightful paradox at the heart of our relationship with domestic cats. Observe them closely and you’ll witness a creature capable of transitioning in an instant from a languid, purring ball of fur draped across your lap, to a focused hunter, eyes narrowed, muscles coiled, stalking an errant dust bunny or a strategically placed toy mouse with a focus that would rival any jungle predator. This duality, this blend of the wild and the domestic, is what makes cats so endlessly fascinating, and explains, perhaps, their extraordinary popularity as pets across the globe. They grace our homes, our laps, and our social media feeds in staggering numbers, captivating us with their grace, their independence, and their sometimes baffling behaviors. But how did these creatures, with their undeniable echoes of wildness, find their way from untamed landscapes into our living rooms? The story of the domestic cat is a captivating evolutionary journey, a winding path that stretches back millennia, tracing the transformation of wild ancestors into the cuddly, quirky, and cherished companions we know today. This article will delve into this remarkable history, exploring the wild roots of our feline friends and charting the subtle yet profound evolutionary shifts that have allowed these once-wild hunters to thrive in the very heart of human homes, forging a unique and enduring bond with us along the way.

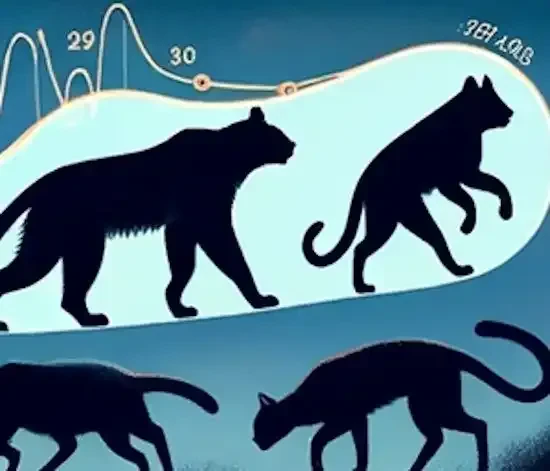

To understand the domestic cat, we must first journey back to their wild origins, to a creature that still roams parts of the world, carrying within it the blueprint for all domestic felines – the African Wildcat, Felis lybica. This species stands as the recognized progenitor of every purring companion that graces our sofas today. The African Wildcat’s natural habitat is as diverse as the continent it calls home, ranging across North Africa, venturing through the Middle East, and reaching into parts of Asia. This encompasses the famed Fertile Crescent, a region often considered the cradle of civilization, and, as we will explore, a pivotal location in the story of cat domestication. To truly appreciate the transformation, we must understand the characteristics of these wild ancestors. African Wildcats are, by nature, solitary hunters. Independence is etched into their very being. Unlike social predators like lions or wolves, they stalk and hunt alone, relying on stealth and agility to secure their prey. Their activity patterns are predominantly nocturnal, or more accurately, crepuscular, meaning they are most active during twilight hours – dawn and dusk – a rhythm deeply ingrained for hunting under the cover of reduced light. Their diet in the wild is dictated by their hunting prowess and the available prey: primarily small rodents, a crucial detail in the story of domestication, alongside birds, insects, and other small vertebrates they can successfully ambush. Physically, they are perfectly adapted to their wild environment – lithe and agile bodies designed for swift movements and silent approaches, sharp senses honed for detecting the faintest rustle in the undergrowth, and physical traits perfectly sculpted for survival in their native landscapes. Territoriality is another key aspect of their wild nature. African Wildcats are territorial creatures, marking and defending their hunting grounds through scent marking, a behavior still evident in our domestic cats, though often redirected to scratching posts and furniture. Understanding these fundamental traits of their African Wildcat ancestors provides the essential foundation for grasping the nuances of cat domestication.

The story of cat domestication is unlike that of many other species we’ve brought into our lives. It’s not a tale of forceful control or directed breeding in its initial stages, but rather a more nuanced narrative of mutual benefit, often described as "mutual domestication." This concept highlights that cat domestication was less of a human-driven project and more of a gradual partnership, evolving organically from a symbiotic relationship. Pinpointing the exact timeline is a continuous process of archaeological discovery and genetic research, but key periods and pieces of evidence illuminate the path. The Neolithic period, with the dawn of agriculture and settled human societies, marks a significant turning point. As humans transitioned from nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyles to settled agricultural communities, they began storing grain. These grain stores, unfortunately, became magnets for rodents – mice and rats thrived in these new, readily available food sources. And where rodents flourished, so too did wildcats, drawn to this concentrated abundance of prey. This is where the story of domestication likely begins. Archaeological evidence offers intriguing glimpses into this early association. A particularly compelling find is the discovery of a cat buried alongside a human in Cyprus, dating back approximately 9,500 years ago. This predates agricultural settlements in Cyprus, suggesting that this human-cat association was already developing, and that the relationship was more than purely utilitarian, hinting at a deeper connection beyond simple pest control. The story truly blossoms in Ancient Egypt. Here, cats ascended to an elevated status, interwoven with religious beliefs and cultural significance. They were revered, associated with deities like Bastet, the goddess of home, domesticity, and cats. Ancient Egyptian art is replete with depictions of cats in domestic settings, indicating a deep level of integration into human life. Mummified cats and evidence of elaborate burials further underscore their revered position. Ancient Egypt provides some of the clearest early evidence of a truly domesticated cat, beyond a simple tolerated wild animal.

But why did this symbiotic relationship emerge? What drove wild, independent African Wildcats to forge a connection with humans? The primary driver was undoubtedly rodent control. Wildcats are highly efficient hunters of rodents, and early agricultural societies were plagued by these pests, which decimated grain stores and spread disease. The natural hunting prowess of wildcats offered a valuable, organic form of pest control around human settlements and grain storage facilities. Crucially, the initial stages of cat domestication were likely characterized by less direct human control than seen in the domestication of livestock or dogs. Humans didn't likely actively "domesticate" cats in the traditional sense of forced breeding and directed selection in the beginning. Instead, it was more likely a process of tolerance and encouragement. Humans, realizing the benefit of having wildcats around to control rodents, likely tolerated their presence, perhaps even indirectly providing a food source not just through attracting prey, but potentially through discarded food scraps. This dynamic created a mutual benefit. Cats gained access to a reliable food source – the rodents drawn to human settlements – and a potentially safer environment, with some protection from larger predators within the vicinity of human communities. Humans, in turn, benefited from the free and efficient pest control services provided by these wild felines. This mutually beneficial arrangement, this subtle dance of tolerance and shared advantage, laid the foundation for the long and evolving relationship between humans and cats.

Over millennia, this symbiotic partnership has subtly reshaped the domestic cat, leading to evolutionary changes, though perhaps less dramatic than in some other domesticated species. Genetic analysis reveals fascinating insights into these transformations. One striking finding is the limited genetic divergence of domestic cats from their wildcat ancestors. Compared to the profound genetic differences between wolves and domestic dogs, cats show relatively less genetic separation from African Wildcats. This suggests a more recent domestication process, and possibly a less intense or directional human influence on their genetic makeup. However, genetic studies have identified specific genes that appear to have been under selection during domestication. These genes often cluster around behavioral traits, particularly those related to tameness, reduced aggression, and increased tolerance of both humans and other cats. This genetic nudge towards sociability and reduced fear is crucial in allowing these once-solitary hunters to adapt to living in close proximity to humans and, in many cases, other feline companions. Interestingly, genes controlling coat color and patterns have also undergone significant diversification in domestic cats. The striking array of coat colors and patterns we see in domestic breeds – calico, tabby, Siamese points, and countless others – are largely absent in wild African Wildcat populations. These variations emerged through genetic mutations and were likely favored, consciously or unconsciously, by humans over time, contributing to the diverse appearances we see today. While genetic changes related to digestion are less pronounced, subtle shifts may have occurred in domestic cats, potentially related to starch digestion or a broader tolerance for different food sources as their diets shifted from strictly wild prey to include human-provided food.

Behavioral adaptations are perhaps where the evolutionary shifts in domestic cats become most apparent. One of the most significant changes is their increased tolerance of humans and conspecifics (other cats). While still retaining a degree of independence, domestic cats are demonstrably more tolerant of human presence and capable of living in closer proximity to other cats than their solitary wild ancestors. The fear response in domestic cats has also generally lessened. Compared to the more inherently cautious and fearful nature of wildcats, domestic cats often exhibit a reduced fear response and increased boldness when navigating human environments. Neoteny, the retention of juvenile traits into adulthood, is a key characteristic of domestication, and is strikingly evident in domestic cats. Prolonged playfulness is a hallmark of neoteny. Adult domestic cats retain the playful behaviors seen in wildcat kittens, engaging in mock hunting, chasing toys, and exhibiting a general playful disposition throughout their lives. Increased vocalization, particularly meowing, is another neotenous trait. Domestic cats meow frequently, but remarkably, this vocalization is primarily directed at humans. Wildcats, particularly adult wildcats, meow far less frequently, using meows primarily as kittens to communicate with their mothers. Domestic cats seem to have amplified and repurposed meowing as a form of communication specifically to interact with humans. Dependency and affection seeking are also neotenous traits seen in domestic cats. Domestic cats often exhibit more dependency on humans for care and affection than their wild counterparts, actively seeking human attention and exhibiting behaviors like rubbing, purring, and kneading to solicit interaction. Communication itself has evolved. Purring, while present in wildcats, may be used more frequently in domestic contexts for bonding and communication with humans. Meowing, as mentioned, becomes a primarily human-directed vocalization, a language developed to bridge the communication gap between species.

Physically, the changes are more subtle, yet still discernible. Domestic cats tend to be slightly smaller on average than their African Wildcat ancestors, though this is not a dramatic size difference, and the range of sizes within domestic cat breeds is now quite vast. The most visually striking physical change is the explosion of variety in coat colors and patterns. Genetic mutations, coupled with later selective breeding by humans, have resulted in a breathtaking array of coat colors and patterns – from solid colors to intricate tabbies, pointed patterns, and everything in between – far exceeding the relatively limited coat variations seen in wild African Wildcat populations. Subtle changes in skull and teeth morphology may also have occurred during domestication, though these are generally less pronounced than in some other domesticated species, reflecting the less intense selective pressures applied to cats compared to animals like dogs or livestock.

Over time, the human-cat bond has transcended mere utility. While rodent control was undoubtedly the initial catalyst, the relationship has deepened and evolved far beyond this practical benefit. We now value cats not just for what they do for us, but for who they are – as companions, as sources of comfort, and as members of our families. Throughout history, the perception and role of cats in human societies has been a fascinatingly shifting landscape. In Ancient Egypt, as mentioned, they were practically deities, revered and worshipped. Medieval Europe saw a more fluctuating view, with periods of negative association, particularly with witchcraft and superstition, leading to persecution in some instances. Yet, even during these times, their practical value in controlling rodents persisted, ensuring their continued presence. In the modern era, we have witnessed a global resurgence and explosion in the popularity of cats as pets. This reflects a fundamental shift towards valuing them primarily as companions, appreciated for their unique personalities, their comforting presence, and the special bond they offer. But why, in the modern world, have cats become such beloved pets? Several factors contribute to their enduring appeal. Their relative independence and perceived low maintenance, compared to dogs, is a significant draw for many. They don't require walks, and while they crave attention, they are also content with periods of solitude, fitting well into busy modern lifestyles. Their natural cleanliness and self-grooming habits are also highly appealing, making them well-suited to indoor living. Despite their independent streak, domestic cats are undeniably capable of deep affection and playful interaction. They offer a unique form of companionship, interacting with humans on their own terms, providing affection and playfulness when they choose, appealing to those seeking a more independent yet loving relationship. Their relatively small size and adaptability to indoor environments, from sprawling houses to compact apartments, further solidifies their position as ideal modern companions.

Today, we marvel at the incredible breed diversity of domestic cats, a testament to both natural mutations and human-directed selective breeding. From the naturally occurring variations that gave rise to breeds like the Maine Coon and Norwegian Forest Cat, to deliberately created breeds with specific physical traits and temperaments, the spectrum of domestic cat breeds is remarkable. However, modern cat ownership also comes with its own set of challenges and responsibilities. Responsible breeding practices and a focus on genetic health are increasingly important considerations in cat breeding. The ongoing debate about indoor versus outdoor living for domestic cats continues, and cat owners grapple with decisions about balancing safety, natural behaviors, and environmental enrichment. Addressing behavioral issues related to domestication, such as scratching, inappropriate elimination, and stress-related behaviors, requires understanding their evolutionary roots and providing appropriate outlets for their instincts within the domestic environment. Despite these modern challenges, the enduring bond between humans and domestic cats remains as strong as ever. Their journey from wild African hunters to beloved house pets is a testament to the power of mutualism, adaptation, and the enduring appeal of a creature that still carries a whisper of the wild within its purring heart. They continue to enrich our lives, offering companionship, comfort, and a constant source of fascination as we marvel at the wild spirit that still flickers within our domesticated feline friends.